A new tax on homes worth more than £2 million was announced yesterday but there are questions over how much it will yield in a Budget where politics trumped economics.

Following months of briefings, trial balloons and an emergency press conference, it was fitting that the details of the Budget emerged in a leak an hour before the main event.

When the Chancellor did speak, it was to announce a £26 billion smorgasbord of tax rises to help fill the Treasury’s black hole and more than double its financial headroom.

As expected, what was on offer was more appetising for Labour MPs than the wider electorate or financial markets.

PARLIAMENTARY POWER

The trajectory was set in the summer, when the government failed to cut welfare spending to the extent it wanted due to a backbench revolt.

The power of the Parliamentary Labour Party was on display again this month when it forced a rethink inside the Treasury on raising income tax in the Budget.

The result of that latest U-turn is the piecemeal approach we saw yesterday. One that spreads the load but comes with a risk of unintended consequences and means plans could unravel.

The lesson of how seemingly trivial changes don’t always survive contact with reality was one that George Osborne learned with his ‘pasty tax’ in 2012.

This time round, it was a tax on high-value homes rather than hot takeaway food.

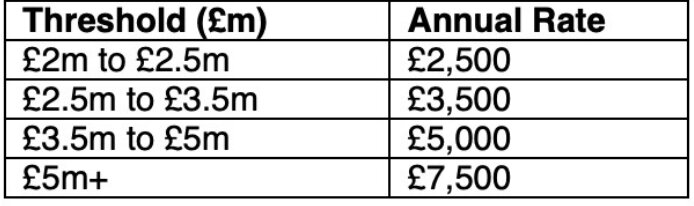

Rachel Reeves announced an annual surcharge on homes worth more than £2 million from April 2028, which will be paid to central rather than local government and be called the High Value Council Tax Surcharge.

FOUR PRICE BANDS

The government has announced a consultation on reliefs, exemptions and deferrals and the OBR has factored in lower stamp duty receipts as a result of extra friction in the housing market.

The plan aims to raise £400 million by 2031, which Pepperstone analyst Michael Brown described as “paltry”.

“For markets the big issue with the Budget is going to be that all the spending is front-loaded but all the tax hikes are back-loaded,” he added.

Until the new scheme is introduced in April 2028, buyers and sellers face uncertainty, especially around price thresholds.

Even once valuations are completed, they could be challenged, which would prolong the limbo.

“The other risk is the precedent of a new tax.”

Over time, more properties will get dragged into the mansion tax net, which means the proportion of terraced houses, flats and semi-detached homes will grow, particularly in the capital.

The term ‘mansion tax’ will increasingly feel like a misnomer.

There are currently 150,000 properties worth in excess of £2 million in England and Wales, but we estimate the number will rise to 180,000 by 2028.

For context, it is also worth remembering that the UK already pays the highest percentage of property taxes among developed OECD countries.

The new policy throws a spanner into the works of the housing market for not much in return.

Like other announcements yesterday, it feels primarily designed to keep backbenchers happy and ensure the near-term survival of the Chancellor and the Prime Minister.

UPWARDS PRESSURE ON RENTS

Elsewhere, it was announced that there will be a two-percentage point increase to rates of property income tax from April 2027, which is estimated to raise £500 million per year from 2028/29.

The OBR said it would “reduce returns to private landlords, following successive measures over the past 10 years,” and would put upwards pressure on rents as more of them sold and supply fell.

The other measures include the Renters’ Rights Act, which will be introduced in May and create added uncertainty around rent increases, repossession rules and the selling process.

In simple terms, politics have again trumped economics, with tenants ultimately footing the bill.

It was a point underlined by the Leader of the Opposition Kemi Badenoch in her Budget response speech.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

For the wider economic picture, the Budget has three major implications, according to Michael Brown.

First, slower growth thanks to tax rises and lower levels of confidence. Other tax hikes announced included extending the freeze on income tax thresholds, charging National Insurance on salary-sacrificed pension contributions and gambling tax changes.

The second effect is more slack in the labour market due to the higher costs faced by businesses as a result of measures like the National Living Wage increase.

“The final impact is likely to be higher inflation.”

The final impact is likely to be higher inflation as minimum wage increases are passed on. “It raises questions as to whether the Bank of England’s projection of inflation falling below the 2% target in Q2 2027 still seems realistic,” Brown said.

Gilt yields were largely unmoved following the Budget, no doubt encouraged by the news that the Chancellor’s headroom was projected to rise from £10 billion to £22 billion.

“Besides some choppiness on the early OBR release, the pound and Gilts were relatively unfazed by the Budget, with the pitch having been heavily rolled beforehand,” said Brown.

POLITICAL FUTURE

The other important consideration is what this means for the political future of Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer.

Provided there is no unravelling in the short-term, the answer has to be ‘safe for now’, given how tailored this Budget was for the backbenches.

Whether that remains the case after the local elections next May is a very different question.