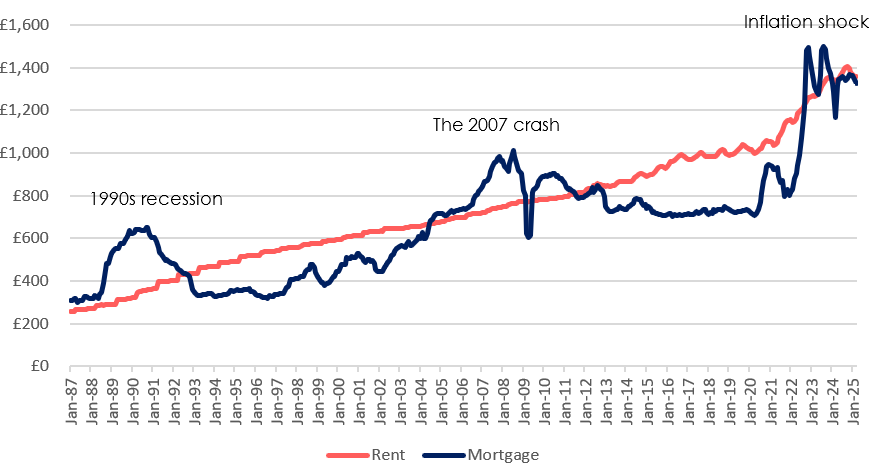

The monthly cost of buying a home in Great Britain has converged with the cost of renting for the first time since the aftermath of the 2022 mini-Budget, according to the latest research by Hamptons.

As the housing market enters a new phase shaped by monetary easing and regional divergence, the decision between renting and buying remains highly dependent on geography, deposit size, and borrower risk profile.

But with borrowing costs slowly retreating and rental inflation cooling, a more stable – if still stretched – affordability landscape may be taking shape.

The shift marks a return to the long-term norm where renting and buying closely track each other in terms of affordability – but this national trend conceals notable regional disparities.

CHEAPER OPTIONS

For a first-time buyer with a 10% deposit, today’s average mortgage rate of 5.11% puts the typical monthly repayment at £1,328, just below the average rent of £1,356.

Source: Hamptons / Bank of England

Two years ago, that same buyer would have been paying £48 more per month than a renter due to the sharp rise in mortgage rates that followed the Bank of England’s tightening cycle.

Historically, buying has tended to be the cheaper option. Since 1987, there have only been three sustained periods when renting was the more affordable choice – each coinciding with a spike in mortgage costs rather than any meaningful drop in rents.

The first was in the early 1990s, when interest rates climbed to 15%. At that time, a buyer with a 10% deposit faced monthly repayments of £649 – nearly double the average rent of £358. This trend reversed as rates fell later in the decade and through the early 2000s.

GLOBAL FINANCIAL CRISIS

The second period came in the wake of the 2007 financial crisis, as lenders raised rates on high loan-to-value mortgages, tipping the scales in favour of renting until around 2010. The most recent instance followed the turbulence caused by the 2022 mini-budget, which sent mortgage rates soaring once more.

Yet while costs have equalised nationally, a deeper dive into the data reveals a distinct geographical split. In all four southern regions – London, the South East, South West, and East of England – renting remains cheaper than buying. In contrast, across the Midlands, North of England, Scotland, and Wales, owning a home is still typically more affordable on a monthly basis.

COST-EFFECTIVE

London stands out in particular. Renting in the capital has been more cost-effective than buying since July 2022, when average mortgage rates were still just 3.69%. Today, a would-be first-time buyer in London would pay £115 more per month to own rather than rent. The high absolute cost of homes in the capital means buyers with modest deposits are especially sensitive to rate changes.

This regional divergence is explained by the way interest rates affect affordability at different price points. In higher-value areas, smaller changes in mortgage rates can quickly tip the scales. For example, mortgage rates of just 4.6% in London are enough to make renting and buying equal in cost. In contrast, in the North East, rates would need to rise above 6.0% before buying becomes more expensive than renting.

SERVICING INTEREST

Crucially, the bulk of mortgage payments in the early years of a loan still goes toward servicing interest rather than paying down capital. At today’s average mortgage rate of 5.11% (on a 30-year term with a 10% deposit), it takes 16.5 years before the repayment portion of the monthly mortgage exceeds the interest.

At the peak of last year’s rate cycle, when rates reached 6.57% in August 2023, that breakeven point extended to 19.5 years. At that point, 86% of a borrower’s first monthly payment went toward interest.

By contrast, in March 2022, when the average mortgage rate was just 2.38%, capital repayments outweighed interest after only one year. Over the full term, a buyer locking in that lower rate would pay 69% less interest – a difference of £206,000 – compared to someone taking out a mortgage at 6.57%.

STABLE RENTS

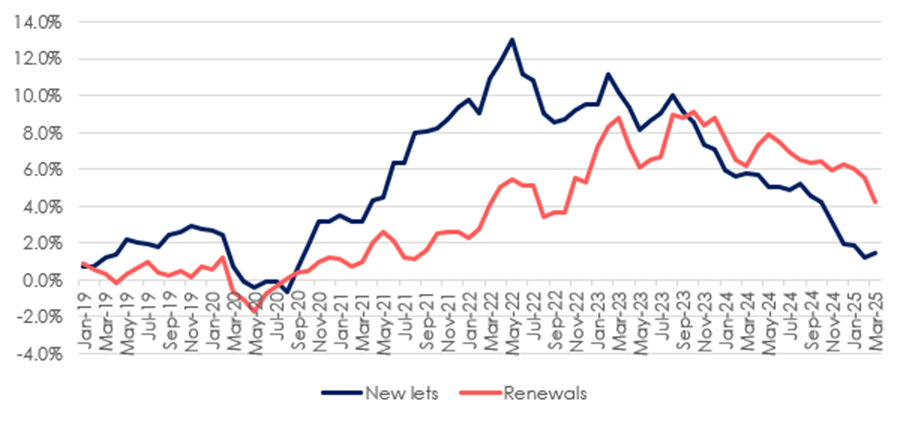

Meanwhile, rents are showing signs of stabilisation. Over the 12 months to March 2025, the average cost of a newly agreed tenancy rose by 1.5% to £1,356 per month. This is the third consecutive month of sub-2% annual growth, and the fifth month in a row where rental increases have lagged behind general inflation (CPI).

Source: Hamptons

In contrast, the cost of renewing an existing tenancy has risen more quickly – up 4.2% year-on-year to £1,250 per month. Renewed tenancies are now, on average, £106 per month cheaper than new lets.

Since September 2023, renewed rents have consistently grown faster than those for new tenancies, suggesting that affordability pressures are increasingly limiting landlords’ ability to raise prices for incoming tenants.

London continues to weigh on the national average. Rents in the capital fell 1.7% over the past year, driven by a 4.4% decline in Inner London. Outer London bucked the trend slightly, with rents rising 1.2%. The average cost of a newly let home in London is now £2,255 per month – the lowest level in nearly two years.

INFLATION SHOCK UNWINDING

Aneisha Beveridge, Head of Research at Hamptons, says: “Since the 1980s, it’s typically taken an economic shock for renting to drop materially below the cost of buying.

“When this happens, it’s almost always driven by the cost of buying rising rapidly, pushed up by mortgage rates jumping for those with smaller deposits who are perceived to be riskier borrowers when prices may fall.

“But we are now seeing the impact of the inflation shock unwinding.”

LESS VOLATILE

And she adds: “Relative to the cost of paying a mortgage, rents tend to be much less volatile. Typically, they’re tightly tied to both wages and inflation.

“This means that while they rarely fall, they also tend to rise more slowly unless general inflation escapes its 2% target. When this happens, rents are often driven up by the higher costs faced by landlords, like we saw in 2022–2023, ranging from higher mortgage payments to bigger bills from tradesmen.

“Should central banks perceive an emerging trade war as a growing threat to economic growth, it could create room for faster rate cuts.

“This could translate into falling mortgage rates, potentially cutting the cost of both buying and potentially renting too. Given these costs form a large part of official inflation statistics, this would put material downward pressure on the headline inflation figure.”